Exploring the rich heritage of an African empire

Oliver Gilkes travelled to the land of the Grand Negus, or king of kings, to explore this vast country’s unique archaeological heritage

Ethiopia must be one of the most misunderstood countries on the planet. More than twice the size of Germany and France combined, with soaring mountains, wide freshwater lakes, endless plains, and a history that traces a direct lineage to King Solomon, it includes a multiplicity of peoples, languages (over 80), and faiths. Once a grand empire, today Ethiopia is a proud republic – and a developing land.

The modern capital Addis Ababa is the culmination of its imperial history. It was founded by the conquering emperor Menelik II in 1886, and has seemed to be in the throes of permanent rebuilding ever since: vast new buildings, highways, and boulevards are laid out among the shacks and shanties of an older Africa.

Even older are Ethiopia’s most ancient archaeological remains. The pioneering work of the Leakey family has put the region at the centre of the study of human evolution. Lucy, the 3.2 millionyear- old ancestor of us all, found by US archaeologist Donald Johanson, is on display in a special sealed case in Addis Ababa’s small National Museum, along with a host of early hominid remains.

The geological anomaly of the Great Rift Valley explains the presence of these evolutionary milestones. One site, near Melka Kunture 50km to the south of Addis Ababa, is on the valley-side where the exposed strata permit the investigation of such ancient landscapes. The marvellous ‘open-air’ museum at Gombore was my introduction to these wonders. Exhibition cases of finds are arranged in five traditional Tukul huts, and we were given an amazing opportunity to handle the actual stone tools from the site, which lie on open display in their hundreds.

There are two sites here. One, excavated by a French mission, is a preserved probable butchery floor with tools and animal remains on the surviving surface, dating to about 800,000 years before the present. A rich sequence of overlying strata contained further and later assemblages of tools, made from the omnipresent volcanic rocks and obsidian.

Early origins

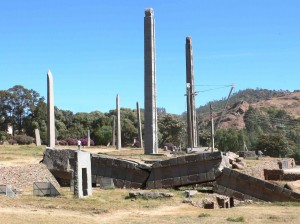

The obelisk park and tombs at Axum. Note the Great Stele that crashed to the ground either as it was being installed, or shortly afterwards.

The historic phases of Ethiopian history are just as archaeologically rich and exciting. The ruins of the capital of the kingdom of Di’amat at Yeha, in modern Tigre, include the fabulous 4th century BC Temple of the Moon, and a nearby pilastered palace similar to Yemeni buildings. The Kingdom of Axum and its heirs were made wealthy by fertile land and then trade. From the 1st century BC, it was the major power of the region, stretching across the straits of Hormuz into Arabia itself. At the centre of the city of Axum is the stele park, one of the few internationally known Ethiopian monuments. Each stele marks a grave – the largest indicating royal tombs – and each is carved as a multi-storey building. The three greatest have a chequered history. The largest lies shattered on the ground, having fallen during its erection or collapsing soon after due to faulty foundations. This is hardly surprising, as it is the single largest stone monolith ever moved by human hands. A second stele was carted off to Rome by Mussolini following the Italian invasion in 1936, but was returned a few years ago, and now stands proudly again adjacent to a third.

legend of the Queen of sheba

Many of Axum’s monuments are traditionally associated with the Queen of Sheba, who stands at the head of the lineage of the imperial dynasty. An ancient reservoir is named as her ‘bath’, while the substantial aristocratic mansion excavated by a French team in the 1970s is inevitably now typed as ‘Palace of the Queen of Sheba’. Ethiopian tradition records that, during the Queen’s famous trip to consult King Solomon, they conceived a son, Menelik I. (The episode finds a place in many of the later and magnificent Ethiopian church paintings.) It was Menelik who, the story goes, spirited away the Ark of the Covenant from Jerusalem, replacing it with a copy.

According to the legend, which lies at the very heart of Ethiopian Christianity, the original now lies in a special church in Axum. And it was here in Axum, in 324, that Frumentius of Tyre persuaded King Ezana to convert to Christianity, making this only the second state, after Armenia, officially to do so.

This tradition was brought home most forcefully during a visit to the painted Maryam monasteries of Lake Tana, source of the Blue Nile, and home of pelicans and hippos. Nearby, the thundering falls of the river can be viewed by crossing the Portuguese Bridge, one of the oldest spans in the country, built of stone by, as the name suggests, the Portuguese allies of the 16th-century emperors. This is the heartland of the Amhara people, the core of Medieval and later Ethiopia. The modern lake-shore city of Bahir Dar, with its palm-lined avenues, is a boat-ride away from these mostly still functioning ancient monastic communities.

The Tana churches are huge, circular Tukul buildings, with thatched or corrugated roofs. A number of them date back to the 14th century, a remarkable monumental Medieval timber-building tradition. A wide outer ambulatory, for the congregation and priests, surrounds the closed central square tabernacle, which, as in all Ethiopian Orthodox churches, contains an unseen copy of the Ark.

The exteriors of these inner shrines are all brightly painted with frescoes of 15th-/16th-century and later date, so that the congregation was faced by an unending cycle of marvellous and instructive holy images: the Passion of Christ, the lives and gruesome deaths of local saints, the story of Mary – who, in local accounts, spent time in Ethiopia, and who is especially revered.

To an archaeologist familiar with the abbeys and churches of Early Medieval Europe and their art, these paintings, made on canvas and attached to the walls, were a revelation: it was like discovering Giotto at Assisi, or stepping into an empty Sistine Chapel for the first time.

After the fall of Axum, the Kingdom of Roha came to prominence, ruled from around 1137 to 1240 by the Zagwe dynasty, who claimed they were the descendants of Solomon and one of the Queen of Sheba’s andmaidens. While they held power, these monarchs left their mark, beginning the construction of the most extraordinary series of rock-cut churches at their capital, the town now known as Lalibela, after their greatest Saint-King.

To call these merely ‘rock-cut churches’ belies the city-sized labyrinth of passages, chambers, tombs, cathedrals, palaces, and chapels, carved like an enormous sculpture from the red granite of the hills. The end result is a representation of heavenly and earthly Jerusalem, with facsimiles of famous shrines of the Holy Land, side by side with deep gullies forming the avenues and roads; there is even a giant, wedge-shaped stairway to heaven, Jacob’s Ladder.

The reasoning here was clear. The actual Holy Land had become difficult to reach following the rise of Islam, and for some centuries Ethiopia was an isolated and mythical land – to Medieval Europe, it was the kingdom of the fabled Prester John. Lalibela was built by its kings to act as a focus for pilgrims, to give an historical and spiritual foundation to a rather dodgy dynasty. Hours of clambering up and down its odd stone stairs and slopes give one an appreciation of their ambition.

The monumental remains of the imperial past are also found north of Lake Tana. The hilltop city of Gondar – one wonders where J R R Tolkien got some of his ideas – almost became the national capital. The dirty and chaotic modern city is centred on a peaceful archaeological park, filled with the majestic ruins of palaces, baths, dining halls, infirmaries, and a concert hall built by the emperors and empresses of the 17th and 18th centuries. There is even a barracks for the imperial lions: those Gondarine emperors had style, sitting in state surrounded by whole prides.

Gondar saw the rise of a glittering court: it was founded by Emperor Fasilides in about 1632, as a new start after the chaos of his father’s rule, which had attempted to impose Catholicism on the land. Rulers like Iyasu the Great built tall, turreted palaces and magnificent churches, the most famous of which – and one of the most strikingly painted buildings in Ethiopia – is Debra Berhan Selassie. Further suburban complexes surround the city: the palace, church, the Library of Empress Mentewab, Fasilides’s giant baptismal pool (still used at Epiphany), and the tomb of his favourite horse.

But Gondar is also a sad place. The strength of the dynasty waned, while that of the great nobles, the Rases, waxed. The last emperors of the early 19th century were reduced to beggary during this ‘time of princes’, living in squalor in the ruins of their once grand apartments. Later rulers, such as Menelik II, preferred power to be focused in their own heartlands away from crumbling Gondar.

We came away with a sense that it is still early days for Ethiopian archaeology: the national science is very much in its infancy. But so many of Ethiopia’s ancient traditions are still living today: its heritage is accepted as an everyday reality, threading seamlessly through modern generations. The experience of an immemorial past and a vibrant and ambitious present that one gets from travelling in Ethiopia is hugely uplifting.